In a hay meadow near Brunswick, Maine:

Bobolink, taking a break from his jumbled singing flights over the field.

Savannah sparrow, keeping an eye on neighboring males.

According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, neither species has been faring well. The bobolink has declined by about 2% per year since the 1960s. The savannah sparrow’s decline is about 1.25% per year.

North American Breeding Bird Survey trend for bobolink, then savannah sparrow (“index” on the vertical axis is a measure of the number of birds seen along annual survey routes):

These declines are typical for meadow species in North America. According to a review by ornithologist Jon McCracken, birds that nest in upland grasslands have, in the last century, “experienced the most pronounced declines of any other group of birds on the North American continent.”

In the last few decades, intensification of agriculture — earlier hay-cutting, more frequent hay-cutting, conversion of grass to alfalfa — has drastically reduced breeding success of these species. Before that, in the mid-1900s, regrowth of forests on former agricultural land was the main cause of the decline of grassland birds. This followed the 1800s and early 1900s, the heyday of hay in eastern North America. Early European colonists cleared large areas of forest, opening grassland. Then, as American agriculture moved to the midwest and heating oils replaced firewood, grasslands in eastern North America declined as forests regrew (and grasslands in the midwest declined as they were plowed for grain crops).

Given the great variability of grassland acreage over the last centuries, the “right” or desirable amount of bird-friendly grassland in the region is obviously hard to state. But the combined effects of early hay cutting (goodbye nests) and land conversion (hello alfalfa fields and housing subdivisions) suggests that, if we want to maintain populations of these species, we’ll need more (and better) grassland than we now have. The economics of farming makes this a significant challenge. Stiff competition from industrialized meat and milk businesses mean that hay meadows are not money-makers, hence the long-term decline.

Stacked along the dock were piles of ceramics, each threaded with ropes or netting. These are octopus traps. Thinking they have found a good rock nook, octopuses slide inside the submerged containers. When the fishermen pull on cords, the jostling alarm causes the octopus inhabitants to hunker down. Fear is their undoing. There is an unfortunate echo of the two-thousand-year-old history of this harbor, as the Carthaginians used a similar strategy of holing up, one that the Romans overcame, ending Carthage’s rule.

Stacked along the dock were piles of ceramics, each threaded with ropes or netting. These are octopus traps. Thinking they have found a good rock nook, octopuses slide inside the submerged containers. When the fishermen pull on cords, the jostling alarm causes the octopus inhabitants to hunker down. Fear is their undoing. There is an unfortunate echo of the two-thousand-year-old history of this harbor, as the Carthaginians used a similar strategy of holing up, one that the Romans overcame, ending Carthage’s rule.

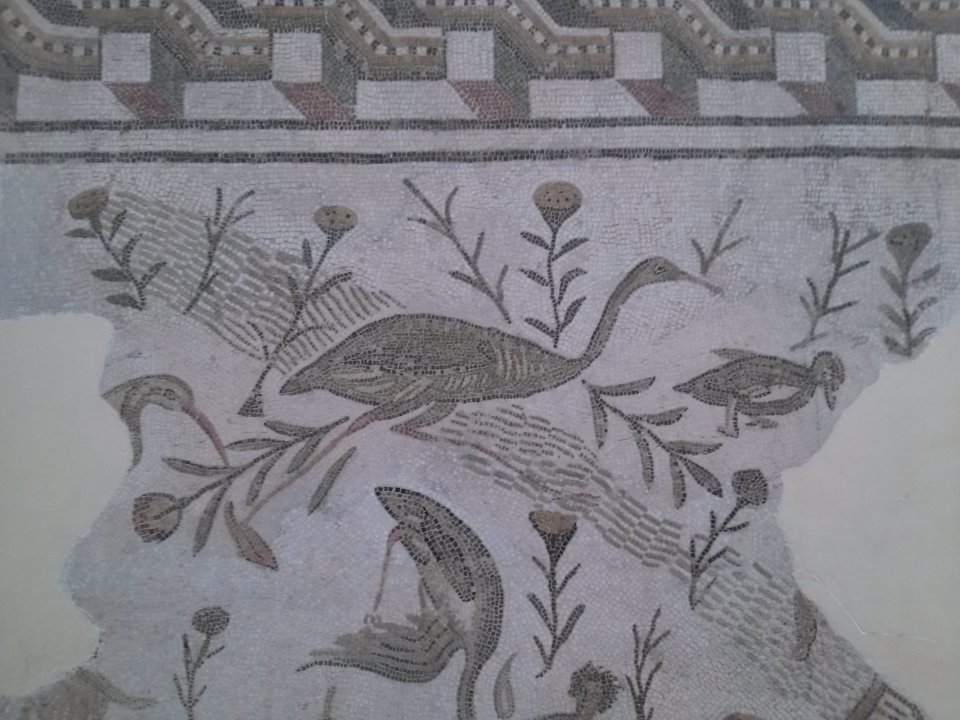

Sadly, the museums are empty of visitors. We walked through hall after hall, alone save for museum employees. The same is true in much of Tunisia. A country whose coasts were thronging (and thonging) beach holiday resorts and whose cultural sites were popular destinations for history and archaeology buffs now receives few foreign visitors. Miles and miles of beach hotels stand completely empty, as if the Rapture had taken away all the lovers of blue seas, discos, and seafood. Historical sites — Roman, Carthaginian, Byzantine, French colonial — are visited by local schoolkids and few others. Two bombings by extremists succeeded in closing down a thriving tourist economy. The terrorists got exactly what they wanted: travel warnings from Western countries that stemmed the flow of foreign money to the only remaining Arab Spring democracy.

Sadly, the museums are empty of visitors. We walked through hall after hall, alone save for museum employees. The same is true in much of Tunisia. A country whose coasts were thronging (and thonging) beach holiday resorts and whose cultural sites were popular destinations for history and archaeology buffs now receives few foreign visitors. Miles and miles of beach hotels stand completely empty, as if the Rapture had taken away all the lovers of blue seas, discos, and seafood. Historical sites — Roman, Carthaginian, Byzantine, French colonial — are visited by local schoolkids and few others. Two bombings by extremists succeeded in closing down a thriving tourist economy. The terrorists got exactly what they wanted: travel warnings from Western countries that stemmed the flow of foreign money to the only remaining Arab Spring democracy.