Drifts of smashed clam shells lie on the exposed rocks at the high tide mark.

These are the leavings of aerial bombardment by herring gulls. As the tide recedes, mud flats are revealed and, buried in the gray ooze, quahog clams. These are big, heavy-shelled creatures, sometimes as large as my hand.

Their interior surface is blushed with purple at one end. Beads made from this colored shells were used as wampam currency by some of the American Indians of this region and, later, by European settlers. In the 17th century, tuition at Harvard could be paid with “1,900 beads of purple quahog and white whelk.” The scientific name of the clam, Mercenaria mercenaria, derives from the species’ importance in human mercantile transactions.

Purple from gastropods was also highly valued on the other side of the Atlantic: Tyrian purple favored by the Imperial elites of the Mediterranean and, later, Christian bishops, came from sea snails. Lately, molluscs have fallen from favor as status symbols, a loss for human aesthetics, but a gain for clams and snails.

As the tide falls, herring gulls gather quahogs from the mud, then fly to the rocky shore:

Just before they reach the rocks, the birds oar their wings to gain altitude, then toss the clam from their beak toward the ground:

The clams accelerate as they fall, but also move horizontally, carried by the forward momentum of the gulls’ flight. The birds know exactly when to release their clams, the crack of impact always falls on rock, even when birds release the clam while still winging over mud or grass. Like humans who can throw a newspaper from a moving bike and always hit the mark, gulls are well-practiced at lobbing their food at the best shell-splitting rocks. On this short stretch of coastline, the birds have three favorite sites and each one is smothered in shell remains.

The violence of the fall is enough to break open the hard shells of the quahog clams:

Gulls quickly consume clam’s innards, a sizeable meal for a bird (a few large quahogs are enough to make a chowder that will fill a human belly). But the clam’s afterlife continues beyond gull gizzards. Within minutes of a gull’s departure, springtails colonize leftovers, munching on protein and fat:

Then, when the tide returns, algae colonize the leftover shells, gastropods graze over calcium-rich surfaces, and small fish and crabs take refuge under shelly eaves.

Gulls are not the only foragers. People — “clammers” — also follow the tide, raking the mud for quahogs and soft-shelled clams.

Clams are the third largest fishery in Maine, one rife with controversy about the right way to manage clams in the face of invasive predatory green crabs, warming waters, and pollution.

While humans fret (with good reason), herring gulls play (also, I think, with good reason). On warm days, the birds drop then re-catch clams seemingly for the joy of it. The feelings of clams about all this are, as yet, unstudied by students of animal behavior. Complete the aphorism, The unexamined clam is…

Stacked along the dock were piles of ceramics, each threaded with ropes or netting. These are octopus traps. Thinking they have found a good rock nook, octopuses slide inside the submerged containers. When the fishermen pull on cords, the jostling alarm causes the octopus inhabitants to hunker down. Fear is their undoing. There is an unfortunate echo of the two-thousand-year-old history of this harbor, as the Carthaginians used a similar strategy of holing up, one that the Romans overcame, ending Carthage’s rule.

Stacked along the dock were piles of ceramics, each threaded with ropes or netting. These are octopus traps. Thinking they have found a good rock nook, octopuses slide inside the submerged containers. When the fishermen pull on cords, the jostling alarm causes the octopus inhabitants to hunker down. Fear is their undoing. There is an unfortunate echo of the two-thousand-year-old history of this harbor, as the Carthaginians used a similar strategy of holing up, one that the Romans overcame, ending Carthage’s rule.

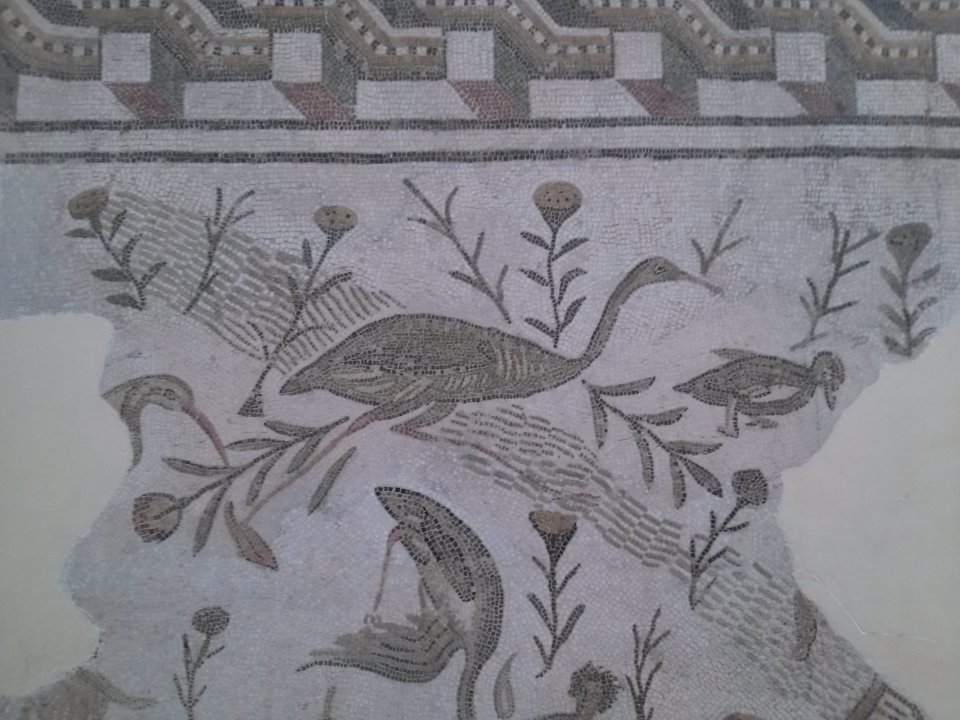

Sadly, the museums are empty of visitors. We walked through hall after hall, alone save for museum employees. The same is true in much of Tunisia. A country whose coasts were thronging (and thonging) beach holiday resorts and whose cultural sites were popular destinations for history and archaeology buffs now receives few foreign visitors. Miles and miles of beach hotels stand completely empty, as if the Rapture had taken away all the lovers of blue seas, discos, and seafood. Historical sites — Roman, Carthaginian, Byzantine, French colonial — are visited by local schoolkids and few others. Two bombings by extremists succeeded in closing down a thriving tourist economy. The terrorists got exactly what they wanted: travel warnings from Western countries that stemmed the flow of foreign money to the only remaining Arab Spring democracy.

Sadly, the museums are empty of visitors. We walked through hall after hall, alone save for museum employees. The same is true in much of Tunisia. A country whose coasts were thronging (and thonging) beach holiday resorts and whose cultural sites were popular destinations for history and archaeology buffs now receives few foreign visitors. Miles and miles of beach hotels stand completely empty, as if the Rapture had taken away all the lovers of blue seas, discos, and seafood. Historical sites — Roman, Carthaginian, Byzantine, French colonial — are visited by local schoolkids and few others. Two bombings by extremists succeeded in closing down a thriving tourist economy. The terrorists got exactly what they wanted: travel warnings from Western countries that stemmed the flow of foreign money to the only remaining Arab Spring democracy.