On Saturday morning, I visited the large ephemeral pond at the end of Brakefield Road. This pond, like all ephemeral ponds or “vernal pools,” fills with water in the early winter, stays wet through the spring, then dries up completely in either summer or early fall. The peculiar hydrology keeps fish out – they obviously can’t survive the dry spells – and creates an incredibly rich community of animals that thrive in the absence of fish predation. The abundance and diversity of salamanders and crustaceans in these pools is unrivalled; many of these species live nowhere else.

Although February has just started, spotted salamanders (Ambystoma maculatum) have already visited the pond, mated, and laid their eggs. The adults of this species lives underground in the surrounding forest and emerge only for a few nights in the spring. After breeding in the ponds, they burrow back down into the leaf litter and disappear from view for another year. This year’s breeding season got going very early. In most years, mating doesn’t happen until late February or early March.

Spotted salamander egg mass seen through the wind-stirred light on the pond surface

I returned later, at night under a misty, drizzly moon, to see whether any salamanders were still in the pond.

Despite a thorough search, I couldn’t find any adult spotted salamanders, but I found dozens of egg masses attached to submerged twigs, especially in the center of the pond where the water was deepest (thigh-high: deeper than I expected). Illuminated with a flashlight these masses are quite stunning. The little embryos are visible within.

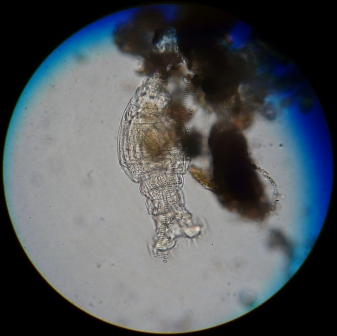

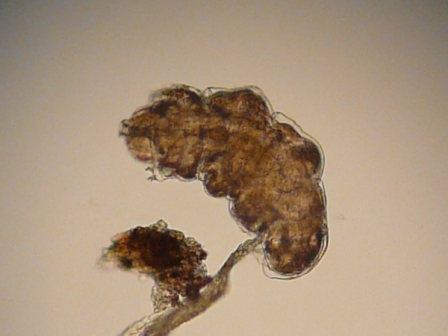

When these spotted salamander eggs hatch, they’ll feed on the diverse set of small crustaceans and larval insects that swarm through the pond’s water. Their cousins, the larvae of marbled salamanders (Ambystoma opacum), hatched in the early winter and have a head start on growth (I posted about a female marbled salamander guarding her eggs in this same pond last fall). This sets the stage for some inter-species struggles: the smaller larvae make good meals.

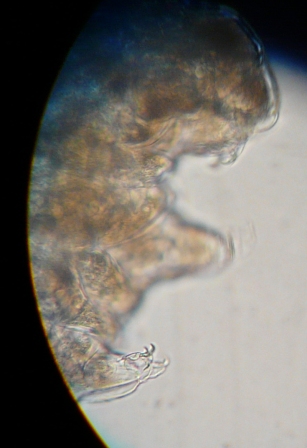

At the shallow end of the pond, I found a few mole salamanders (Ambystoma talpoideum). In our region, this species is found only at ephemeral ponds. Like spotted salamanders, they lay egg masses attached to small twigs in the pond, although the mole salamander has a smaller cluster of eggs (fewer than one hundred, rather than up to two hundred as in spotteds). The adult is also smaller, about half the length of the spotted.

Ephemeral ponds are in trouble – they have no legal protection in most states. The federal Supreme Court SWANCC decision removed Clean Water Act protections from these and other “isolated wetlands”) and these small pools tend not to get protected when residential development, tree plantations, or other habitat modifications happen in a forest. A few states have adopted their own protections, but Tennessee is not one of them, to my knowledge (and I’d be oh so happy to be corrected on that point if some recent legislative action has taken place).

Salamanders were not the only creatures on the move.

Toads were sitting on the paved roads in town.

I suspect that the toads were hunting stranded earthworms, which were everywhere.

Turning the flashlight around for a moment, another wet-skinned night wanderer was seen in the rain.

In closing, I’ll record a new life goal: to get some waders that don’t leak. The gallon or two of water that oozed into my boots was cold, cold. On the other hand: the feeling of icy water around my toes; the utter silence of the woods except for the patter of water drops in the dark pool; the spicy smell of wet leaves on the forest floor mingling with the slightly sulphurous odor of the black, sodden leaves on the pond margins; the feel of rain on my face. These things bring me back to my senses. Reframing: leaky boots are a doorway into experience. A new product line idea for LaCrosse boots?

The sign of a Saturday night well spent: wringing out your socks.