The last few posts have suffered from an excess of coherence and narrative continuity, so here are some true ramblings from Santa Cruz, CA (and for those who are still in awe of planetary motion, my last post also has some new Venus photos from a grad student that I met at the viewing at UCSC who kindly shared his images via email)…

Santa Cruz sits at the intersection of the cold ocean, the foggy redwood forests, and the blazing hot oak savannahs. Walking for thirty minutes in almost any direction will carry you into a new ecosystem. So variegation of microclimate is extreme.

San Francisco was built from lime and wood taken from this area, so almost all the forests are full of redwood trees growing in little clusters around huge, hundred-year-old stumps. The younger trees are still impressive: very very tall. There is almost no light in the understory, so even on a bright sunny noon, you gaze through the aromatic gloom. These trees drink water from the air. Even though their roots are dry, they get enough moisture from the near daily dousing in ocean fog to keep growing even in rainless months. How do we know this? The oxygen isotope ratios in fog differ from those in rain, so plant physiologists can read the isotopic “fingerprint” of oxygen in the trees, then deduce the source of water.

The redwood below has been adopted and turned into a granary by a family of acorn woodpeckers. Each hole is a storage place for an acorn. The family makes its nest in the tree then defends their nest, their stored food, and their honor from other woodpecker families, all of whom are thieves and cheats. Very much like Scotland, with less rain.

Oaks in California are being slammed by “sudden oak death,” a descriptive enough name for the disease (caused by an exotic species of protist, Phytophthora ramorum, the same genus that causes blight in potatoes, die-offs in peppers, and all kinds of destruction in many other tree species). The disease starts as lesions on leaves (these are tan oak leaves)…

…then kills the whole tree in about a year. Most of the tan oaks in the understory seemed to have the disease. (And, yes, I thoroughly washed my shoes on my return to Tennessee).

Other understory plants are doing much better. These are huckleberries, a close relative of the blueberry:

Mountain lions roam the woods and occasionally come into town. Warning signs are dotted over campus and the state parks. It is not clear whether the “no dogs” part of the sign is meant as a statement of a regulation or a summary of the outcome of past events:

The coast is continually raked by an incredible strong cold wind. Seabirds are abundant. These are Brandt’s cormorants:

Snails were common in the sandy coastal scrub. They were all, as far as I could tell, the invasive European immigrant, Cornu aspserum, the same species favored in France for eating:

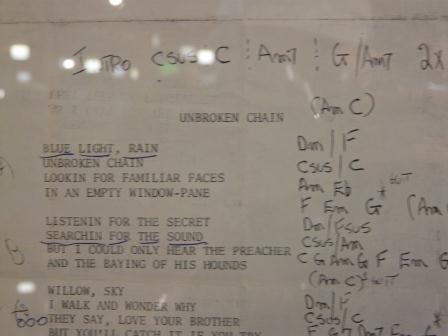

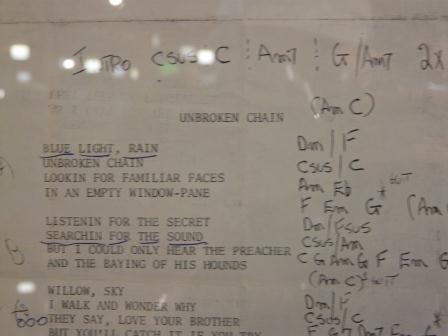

Back on campus, we briefly visited the University library and the Archives of the Grateful Dead, a carefully curated collection of posters, notes, letters, and so forth relating to the band’s long tenure. I was particularly taken by the Ph.D. theses. I know that several of the followers of this blog are Dead fans, so take note: the official opening is coming up at the end of June. There is a slight air of incongruence about an academic archive of Grateful Dead documents, but this strangeness, even dissonance, would have pleased Mr. Garcia, I think.

My visit to Santa Cruz was sponsored by the Department of Environmental Studies and initiated by the graduate students in the department who brought me in as their seminar speaker for this semester. Thank you. And special thank you to Leighton Reid and Rachel Brown who welcomed me and showed me around during my visit.

I’ll close with a shot of a door to a grad student office, chosen almost at random. Sewanee residents may remember those great students who protested the Lake Dimmick development, packing Convocation Hall and speaking with forceful clarity to the Regents. That spirit has now been carried to some far flung parts of the world.