A gray fox swaggered across University Ave this morning, its bushy tail bouncing as it trotted. It was headed to the patch of woodland behind Otey Parish Hall and the Duck River Electric building. I’ve seen fox scat on the road there, so I think this must be a resident, perhaps the same animal that I saw last summer with a rabbit in its mouth.

This has been a busy few months for fox and coyote sightings in Sewanee. Now, a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has added some insight into the tangle of interactions among these wild dogs and their prey. Apparently, tick abundance and Lyme disease risk is affected by the numbers of foxes and coyotes. The paper examines data from the northeast, but its results may also be relevant here.

Lyme disease (caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi) is transmitted to humans by tick bites (especially bites from nymphal stage of Ixodes scapularis, the black-legged tick) But humans are not the main host of these ticks, so the abundance of ticks is determined by the abundance of their other mammalian hosts, especially mice. Foxes and coyotes both prey on mice, so you’d think that more foxes and more coyotes would mean fewer mice, and therefore fewer ticks, and therefore fewer Lyme disease cases. But things are not quite so simple.

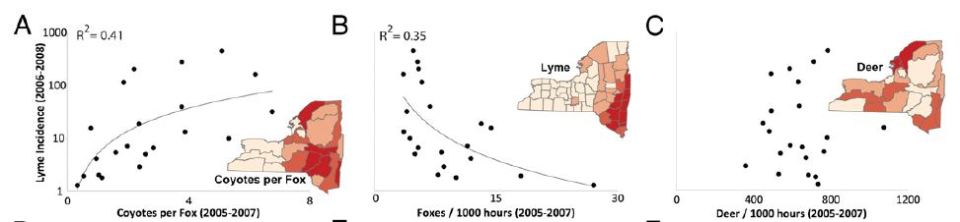

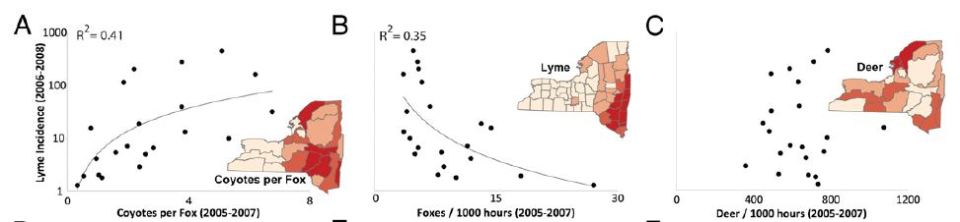

The abundance of foxes is indeed correlated with a decreased risk of Lyme disease. Foxes love to eat mice and fox populations can get quite dense, so mice fare poorly in areas with healthy fox populations. Coyotes also eat mice, but coyotes live at lower population densities than foxes. Coyotes also drive out foxes. So the overall effect of coyotes on Lyme disease is a positive one: more coyotes = fewer foxes = more mice (despite the few that get eaten by coyotes) = more ticks = more Lyme disease. And deer? There was no correlation with Lyme disease; mouse abundance drives the dynamics of the disease and deer abundance seems to have little effect (except in areas that have no deer — an unusual situation these days — that do have lower incidences of Lyme).

Excerpt from one of the paper’s figures, showing correlations (or lack thereof) between Lyme disease and either coyotes per fox (positive correlation), foxes (negative correlation), or deer (no correlation).

An important caveat: this paper examined correlations among estimates of the abundance of different animals. But correlations are slippery things. They seem to imply that we’ve discovered a cause-and-effect relationship, but this is often misleading. So I’m sure this story will evolve as scientists tease out the subtleties (does the effect of foxes depend on the availability of other prey?) and alternative explanations (might some unknown causative third variable be correlated with coyotes and Lyme?). I wonder how domestic cats play into all this. They are major predators on mice and often live at densities well above what could be supported without the subsidy of store-bought cat food. Do they also suppress Lyme?

Some notes for blog readers in the south:

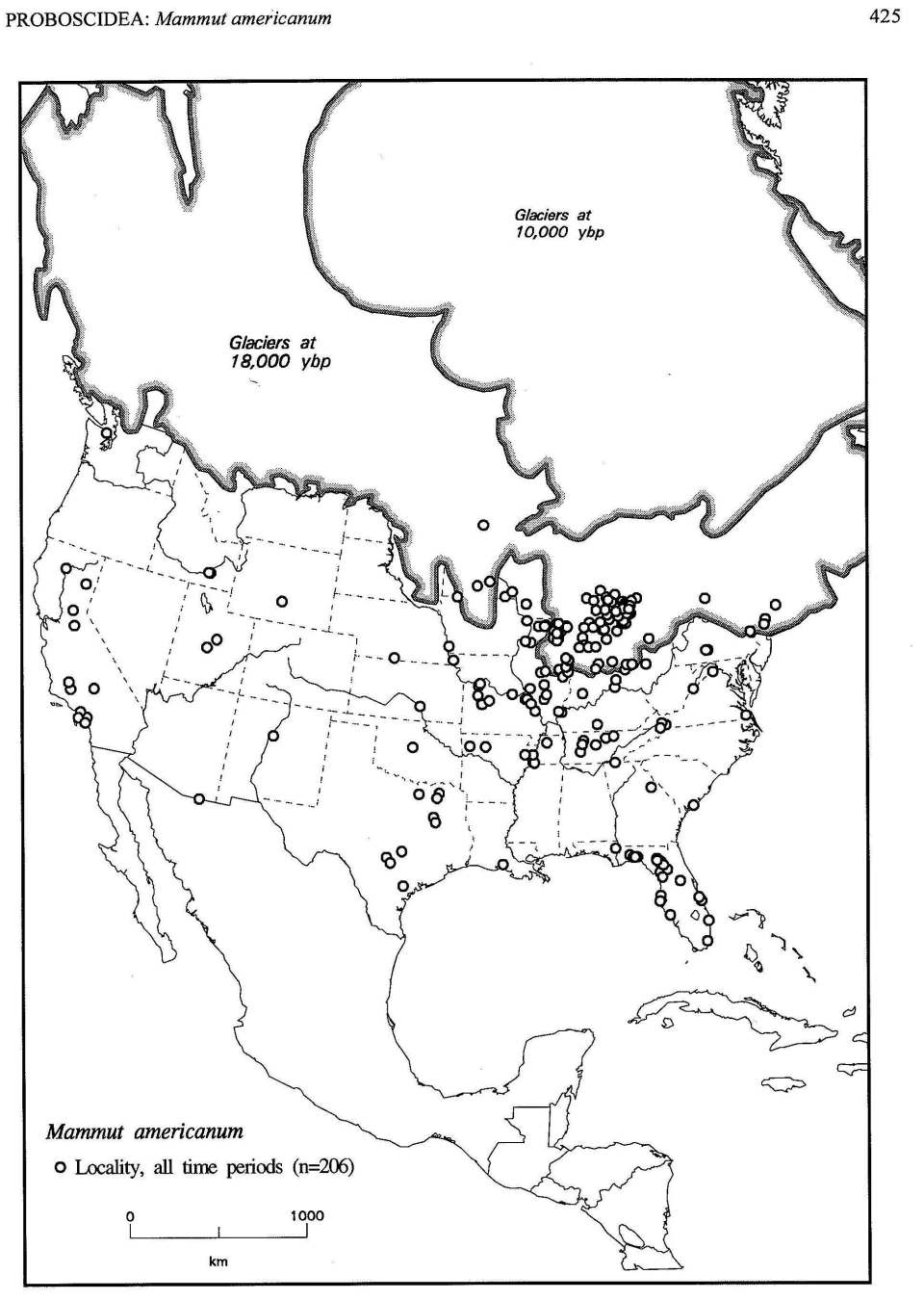

1. We’re well outside the “hotspot” of Lyme disease, as shown on this CDC map. The disease does not seem to be increasing in many parts of the south. But, in Virginia and other areas that are close to the center of Lyme’s activity, the disease is increasing quite rapidly.

2. The south is blessed with other tick-borne diseases. Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness is one; Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is another.

3. Although we do have black-legged ticks here, lone star ticks and dog ticks are more common. These are not prime carriers of Lyme, but they can transmit the other tick-borne diseases.

For more info about ticks, the CDC site has some good links and great pictures (which will make your skin crawl). Obviously, if you have medical concerns about a bite, check in with an MD, not a Rambler.