I spent much of Saturday on a trip organized by the Sewanee Herbarium, led by Paul Davison from the University of North Alabama. In addition to being a botanical expert, Paul is a master of finding the “wee beasties” (a phrase used by the pioneering microscopist Van Leeuwenhoek) that surround us: the micro-world of single-celled protists and tiny animals, all existing just beyond the limits of our vision. But, with some simple equipment and a hand lens or microscope, this world opens up for us. About 24 people came on the trip, a good mix of Sewanee biology students and faculty, along with community members.

Paul Davsion discussing the "pin cushion" moss, Leucobryum.

Curious structures growing in the Leucobryum moss: undescribed in the North American literature, apparently. Perhaps micro-male mosses growing within the larger female parts of the plant (the Archegonia, for lovers of botanico-jargon).

Leafy liverworts creeping across tree trunks.

Seen close, the alternating scale-like flaps (not true leaves) of the liverwort are visible.

After a foray into Lost Cove, we returned to the lab to pull open the door to another world (amazingly, also the same world) by looking at critters under microscopes. We found legions of algal cells, whizzing crustacea, lumbering protists, and gliding flatworms.

By holding my camera up to the microscope lens, I snapped a few shots of a couple of my favorites.

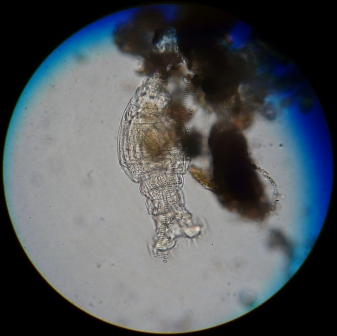

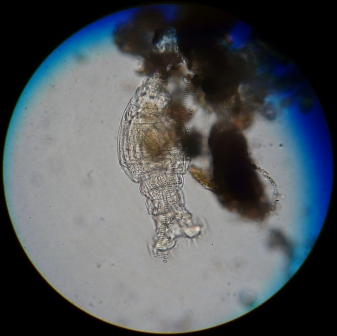

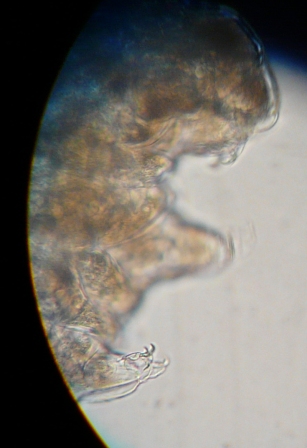

A rotifer, or "wheel animal". Its head is pointing down and its rear end is clasping some dead plant material (aka crud). the two Mickey Mouse ears are ciliated (cilia = hairs that stir the water) feeding devices, moving food into the mouth.

A close look at this shot shows the grinding pharynx that pulverizes food as it moves through the gut (look for the round structure to the left of the "60" mark).

Commercial break: go buy Apple products. Chris Waldrup sent me this photo that he took through the scope with his iPhone. Pretty darn good. Yes, I want one.

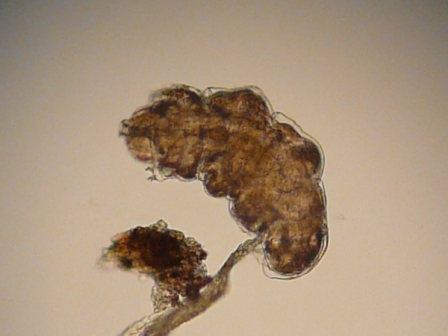

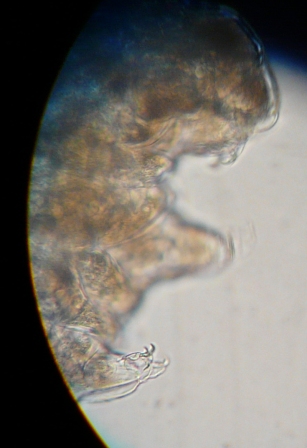

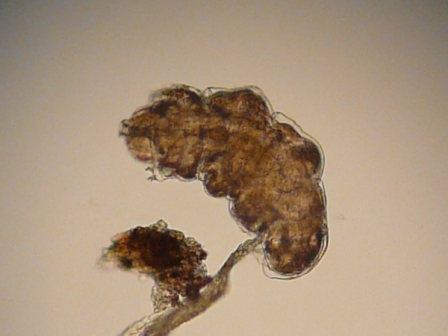

Now for the bear: this is a tardigrade, also called "waterbear" or "moss piglet" (with some crud to the left and below -- the waterbear is at the top). It was indeed living in some moss. They have eight little legs and amble along like bears. This one is stranded on its back with its front legs pointing to the left and its hose-like mouth just visible. Don't let the rolly-poly cuteness fool you: these are the toughest animals in the world, able to enter suspended animation and survive the deepest cold imaginable, vacuums, radiation blasts, utter dryness for years, and exposure to temperatures above the boiling point of water.

Tardigrade feet, equipped with claws for clinging to their mossy homes. They'll still be hanging on when Homo sapiens has turned to a layer of dust in the geological column. So far, tardigrades have been around for 600 million years. Modern humans, less than one tenth of one percent of that.

Thank you, Paul Davison, for leading the hunt. Thank you also to Jon Evans and Mary Priestley for organizing the event.