Taken at dawn a few weeks ago. Perspective is everything.

Category Archives: Archosaurs

Red-shouldered Hawk watching the Abbo’s Alley creek

Late migrant: orange-crowned warbler

The bird was feeding in the dead seed heads of asters and goldenrod this morning, chipping gently to itself.

Compared to other warblers, this species is scarce here. It breeds in the far north of Canada, then winters in the southern U.S., along the Gulf Coast and into Mexico.

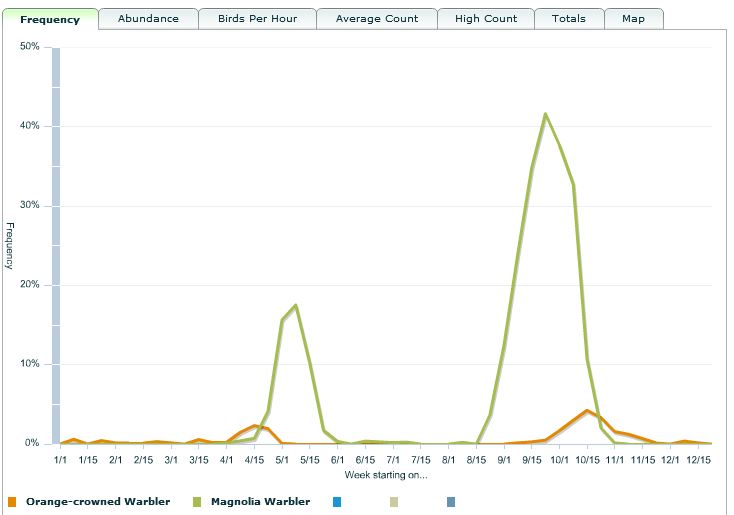

I pulled its occurence data from ebird‘s new graphing tool. The graph below shows how the number of sightings in Tennessee varies through the year. I also included magnolia warbler to give a comparison to a more common migrant species. The orange-crowned warbler generally migrates later in the year and is much less abundant. Even by orange-crowned warbler standards, mid-November seems a bit late.

The seed heads of white heath aster seemed particularly popular choices for the bird’s attention. What tiny spiders, flies, and grubs hide inside these pea-sized flower heads?

Hermit thrush

Appropriately enough for a day in which plans to despoil boreal forests were dealt a blow, the first hermit thrush of the winter showed up yesterday. These thrushes breed in the boreal and mixed forests of Canada and the western U.S., then move south for the winter. They are well-camouflaged against fallen leaves; even their rusty tail looks like a fallen autumn leaf. Once spotted, though, they are easy to identify: unlike other thrush species, the hermit thrush bobs its tail up and down, giving away its identify even when all other field marks are unclear.

Monumental birding

Pine siskin

On the heels (or, more precisely, the hallux) of the purple finch, comes another bird from the north, the pine siskin (Spinus pinus — a scientific name with some poetic potential). This species also arrives in Sewanee in waves that vary considerably in strength from year to year. Perhaps last week’s major snowstorm up north has pushed these birds south?

First purple finch of the winter

Note the very distinctive stripes on the head and the slightly forked tail. The size of the overwintering population here varies considerably. The food supply available in the northern coniferous forests seems to determine how many we get. In hard years, we're swamped with them; in other years, we have none. This one is a female. Males have a purple wash over their head.

Catharsis

A few days ago, a deer died just beyond the fence at the bottom of the garden. A dozen vultures came to the wake.

Turkey vultures arrive first, guided by their excellent sense of smell. Black vultures follow, guided by their excellent sense of entitlement. Black vultures travel in groups, watching for the turkey vultures, then flop down and drive away their keen-nosed cousins.

All vultures have powerfully acidic guts with potent digestive enzymes. In this way, they cleanse carrion of disease. Anthrax and other microbes are killed by passage through a vulture; not much else in nature will kill them. The scientific name of the turkey vulture is therefore apt: Cathartes aura, the purifier.

Autumn, part 2, begins

A vigorous killing frost laid waste to the last of the tender summer plants in the vegetable garden.

I harvested the last of the peppers before they could get zapped,

then planted garlic bulbs in the empty pepper beds.

then planted garlic bulbs in the empty pepper beds.

New birds in the garden today, all refugees from the north that will stay with us for the winter: dark-eyed junco, yellow-bellied sapsucker, and white-throated sparrow.

New birds in the garden today, all refugees from the north that will stay with us for the winter: dark-eyed junco, yellow-bellied sapsucker, and white-throated sparrow.